Rocket Engines That Might Take Us to Mars

Table of contents

You don’t acquire a geeky obsession about technology like ours without growing up being a science fiction fan. While Star Wars fostered an unhealthy fetish for Carrie Fisher in a skimpy slave outfit, Star Trek probably holds a special place in our tiny little MBA hearts. That’s because Gene Roddenberry’s space opera offered a vision of the future where humanity mostly abandoned its petty differences, thanks largely to technological progress, and reached beyond the stars. In particular, the invention of the warp drive, a fictional rocket engine, allowed the USSS Enterprise to travel faster than the speed of light in order to “explore strange new worlds” and to create some #MeToo moments for those sexy blue space aliens.

Unfortunately, we’re far from inventing such rocket engines. Our one piece of hardware that has reached interstellar space, Voyager 1, will take about 17,000 years to cover the distance of one light-year. So, unless we figure out a way to live forever, we’ll forever be space tourists, shuttling rich Russian oligarchs to the moon and back like some high-priced carnival ride until we can build a space engine capable of faster-than-light travel. We’ve covered startups developing various rocket engines for rockets and satellite propulsion systems, but in this article, we’ll dive a bit deeper into some of the more interesting technologies being developed that might launch us beyond the stars.

Rocket Engines Powered by Plasma

There are several types of rocket propulsion. The most common relies on a highly explosive chemical reaction that provides powerful thrust to lift off heavy spacecraft like NASA’s Space Shuttle or the Falcon Heavy from SpaceX. It’s really the only practical way we currently have of punching free of Earth’s gravity. The problem is that those types of rocket engines require a lot of fuel, making them somewhat impractical for the long journey to Mars – unless you think playing games of cribbage for a couple of years with the same six people sounds like a good idea. Ad Astra thinks it can do the journey to the Red Planet in 40 days.

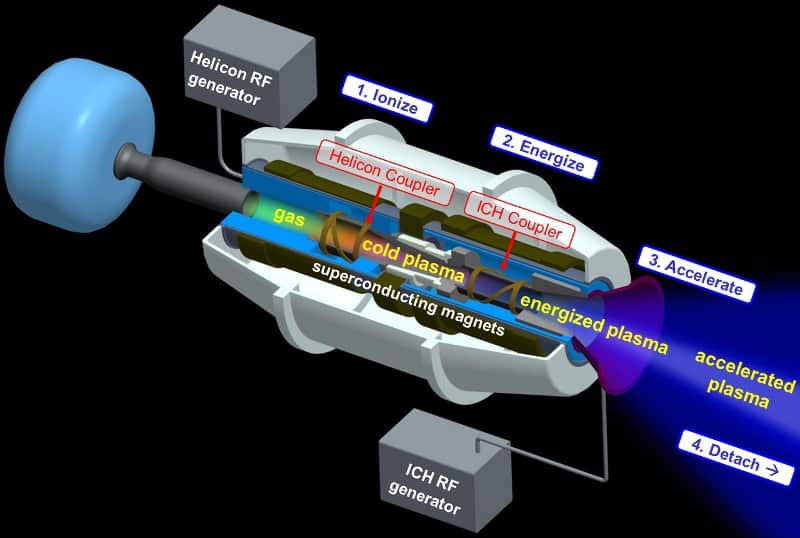

VASMIR is an electric engine, which in itself isn’t anything revolutionary. These sorts of propulsion systems have been used on satellites and even a few deep-space missions. They work by ionizing an inert gas like xenon or hydrogen through an electric charge, creating plasma, a distinct fourth state of matter (the other three are solid, liquid and gas). Electric and/or magnetic fields are then used to direct the plasma to provide thrust. The sun is just a giant ball of plasma, and some of you out there probably own a plasma TV. These engines aren’t capable of sudden bursts of power, like chemical-based rockets, but they are far more fuel-efficient, capable of nearly continuous acceleration. While the retired Space Shuttle could hit speeds of 18,000 mph, a spacecraft powered by plasma rocket engines could exceed 200,000 mph, according to NASA.

Going Nuclear with Rocket Engines

3D Printed Rocket Engines

Speaking of 3D printing: Did you ever notice that whenever the Enterprise got blown to smithereens, by the end of the movie it was already being rebuilt? How did it come together so quickly? No doubt it was through some 24th-century version of 3D printing. One company at the forefront of rocket-related 3D printing is Relativity Space, which finally came out of stealth mode and announced its intentions to 3D print both rocket engines and boosters. Founded in 2016, the Los Angeles-based startup has raised more than $45 million, including a $35 million Series B in March that included billionaire Mark Cuban. No doubt much of those funds will go toward further developing the company’s larger-than-life 3D metal printer, Stargate, and its first 3D printed rocket, Terran, and engine booster, Aeon.

The company says it can build and launch a new rocket in 60 days, using less than 1,000 components versus nearly 100,000 for conventional rockets. That means there are a lot fewer parts that can possibly fail. The company is reportedly lining up some military contracts, along with its commercial business, where it hopes to charge about $10 million per launch. Relativity Space isn’t the only company betting on 3D printing technology for rocket engines. Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings (NYSE:AJRD), which through its aerospace and defense company, Aerojet Rocketdyne, builds rocket engines and missiles that blow stuff up, 3D printed an entire rocket engine four years ago. The company’s next-generation RL10 engine thrust chamber was built almost entirely using 3D printing.

Update 11/18/2020: We profiled Relativity in a piece titled The World’s Largest Metal 3D Printer is Printing Rockets.

Electric-pump-fed Rocket Engines

Founded in 2006, L.A.-based Rocket Lab is also known to use 3D printing technology to build most of its lightweight Rutherford rocket engines. The NewSpace startup has raised $75 million in disclosed funding thus far, and its backers include firms like Khosla Ventures and Bessemer Venture Partners. Designed in New Zealand, the Rutherford rocket (named after the New Zealand-born British physicist, known as the father of nuclear physics) is the only rocket engine in the world that uses electrically driven propellant pumps, rather than turbomachinery, which also makes them less complex and expensive to build. It also uses two propellants, a fuel mixture of highly refined kerosene and liquid oxygen.

The rocket itself, Electron (pictured above), uses the Rutherford engine on both its first and second stages, another cost-saving measure. Its payload is relatively limited at about 500 pounds.

Update 11/17/2018: Rocket Lab has raised $140 million in Series E funding led by earlier backer Future Fund to kick its manufacturing facilities into high gear, enabling the continued aggressive scale-up of Electron production to support their targeted weekly flight rate, build additional launch pads, and begin working on three major new R&D programs. This brings the company’s total funding to $215 million to date.

Back to the Future with Catapults

Apparently turning to the medieval Dark Ages for inspiration, Silicon Valley-based SpinLaunch has raised a total of $40 million to fling cargo into outer space catapult-style. The company took in $35 million from Google, Airbus, and VC firm Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in a Series A last month. The company plans to sidestep the whole messy business of rockets and combustible fuel by developing a kinetic energy launch system that acts as a sort of centrifuge, spinning its payload at incredible speeds in order to launch it through the atmosphere. SpinLaunch is targeting a per launch price of less than $500,000, according to TechCrunch.

Update 01/17/2020: SpinLaunch has raised $35 million in Series B funding to build out its new headquarters and R&D facility in Long Beach and to complete its flight test facility at Spaceport America in New Mexico. This brings the company’s total funding to $75 million to date.

Forget Rocket Engines: Launching Rockets with Drones

Founded in 2016, a startup out of Alabama called Aevum is developing unmanned drone airplanes that can launch small payloads in flight every three hours. Such air-launch systems are not new but the use of a drone, dubbed Ravn, to launch a rocket into space is definitely a new twist on the paradigm. Ravn would operate autonomously, from takeoff to landing, flying like any other sort of commercial jet. The company’s long term goal is to use the Ravn platform to launch numerous communication satellites, bringing global internet to the masses.

Conclusion

There’s more, of course. There’s JP Aerospace, a DIY space program of sorts that has floated the idea of, well, floating its way to near space, by using a type of airship to carry its payloads to the edge of outer space, before using an electric-propulsion engine to go farther. Engineers in Europe are designing a rocket engine that basically eats itself as it accelerates, shedding weight as it blasts into orbit, and thus saving weight. Meanwhile, the European Space Agency has tested a type of plasma rocket engine that can literally live on thin air. The air-breathing electric-propulsion system sucks in air molecules from the edge of a planet’s atmosphere, largely replacing the need to carry a gas propellant at all.

Whether any of these rocket engine innovations will eventually help us to get to Mars or beyond is impossible to say, but it’s quite a ride watching all of these new technologies being developed. They all seem to be quite moonshot technologies as well, and maybe that’s why we have yet to see much in terms of M&A activity by big aerospace companies. Yet. Now that more and more of these NewSpace startups are launching (with some respectable rounds), and developing warp drive-potential rocket engines (maybe), we wouldn’t be surprised if bigger and more frequent acquisitions start to play out in the next few years.

Sign up to our newsletter to get more of our great research delivered straight to your inbox!

Nanalyze Weekly includes useful insights written by our team of underpaid MBAs, research on new disruptive technology stocks flying under the radar, and summaries of our recent research. Always 100% free.

Why is the BFR Raptor not included in here? That seems like the most probable one right now. Also, bad article, looks like some quickly done wannabe BuzzFeed list…